Your Cart is Empty

Artists

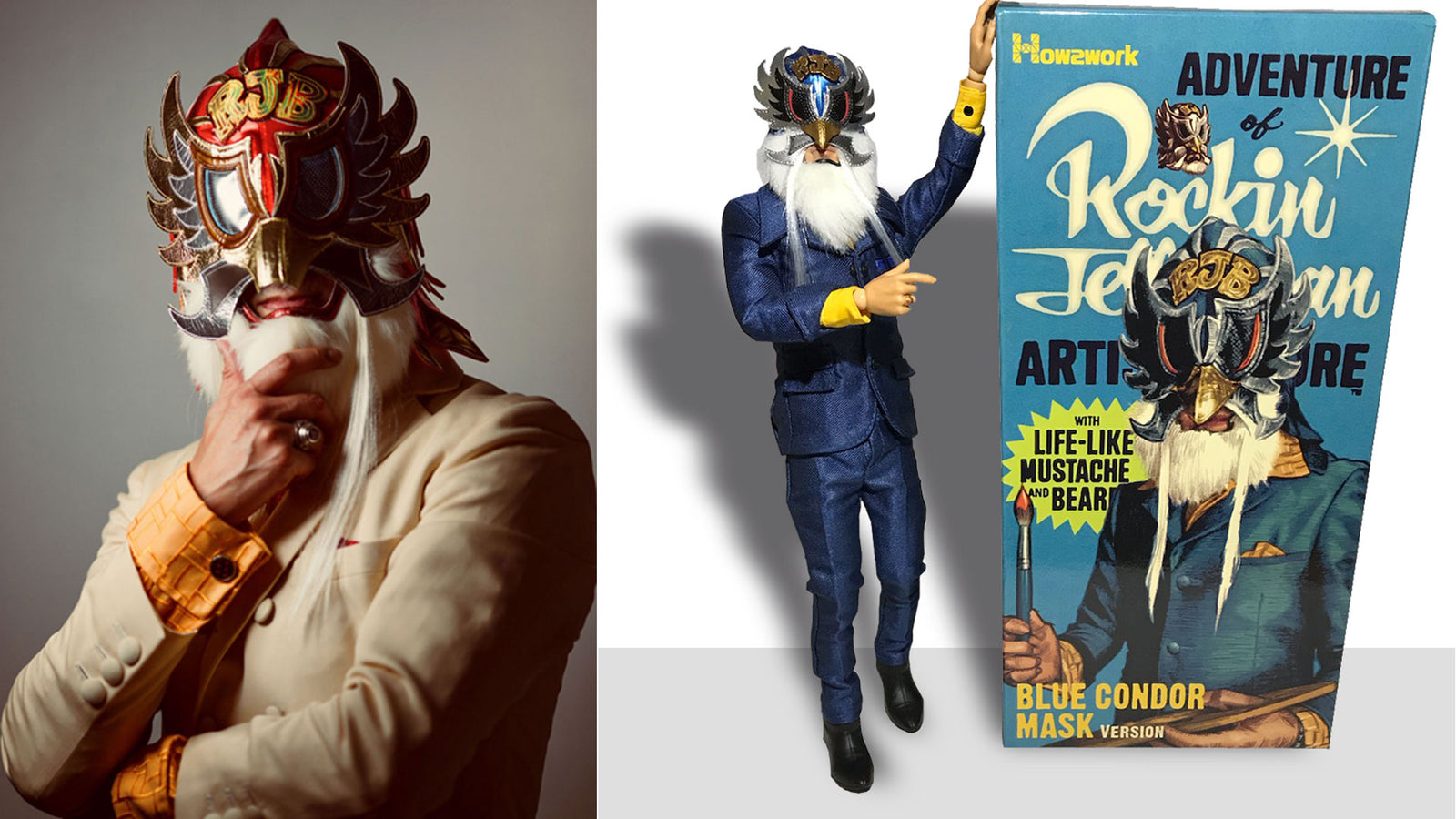

Mondo Jelly: The Anachronistic Desires of Rockin’ Jelly Bean

March 31, 2019 4 min read 0 Comments

Rockin’ Jelly Bean draws from an artistic tradition that clearly fetishizes elements of western pop culture from the 1960s and 70s. His style is Americana refracted through the lens of a Japanese youth voraciously consuming comics, pinups, and rock n roll. Rockin’ Jelly Bean’s also a member of the band Jackie and the Cedrics, a Japanese surf-rock ensemble, preserving a sound and style out of time, but always seductive. Citing his favorite artistic inspiration as “naked women” in interviews, his style is evocative of R. Crumb’s hyper-exaggerated female forms, minus the overt racism, and with some Osamu Tezuka-tinged cartooning added to the mix. RJB’s art style is based on a foundation of stealing his father’s magazines and copying nude photos, according to an interview with Tokyo Otaku Mode. While his exact age is unknown, it’s clear from his affinity for garish colors, feathered bangs, and grindhouse schlock that RJB is a child of the 70s.

Rockin’ Jelly Bean is almost never seen without his signature luchador masks transforming him into a Tiger Mask-esque figure where the canvas of the ring becomes the canvas of the painting (or the canvas in Photoshop). RJB has claimed in interviews that he wears his masks due to a motorcycle accident around 1996 that left his face scarred, a sensitive spot for an artist that revels in the erotic, grotesque, and nonsensical. Rockin Jelly Bean’s career as an illustrator began in the early 1990s, where he made posters and album art for surf rock and punk bands in Japan and LA. This era of his work is evocative of the 90s poster art styles of Frank Kozik and Coop in how it revels in the crude, the irreverent, and the sexy. While Kozik makes use of collage style cartooning, and Coop’s style had rockabilly slickness to it, RJB’s style takes women’s bodies, contorts and exaggerates them, and slaps on the warm glowing colors of a grindhouse theater screen. There is a vein of Russ Meyer’s hyper-eroticism through RJB’s work, the madcap attitude of Big Daddy Roth’s Rat Fink or the over the top arrangement and bold text of an Ilsa She Wolf of the SS poster. The male gaze is strong in RJB, as is his fetishization of American pop culture.

This is not merely reflection of western pop culture, but an amplification and exaggeration that comes from many Japanese artists. RJB’s art is based on how America is personified in Japanese pop culture and imaginations: a realm with no boundaries, massive scale, and carnality spilling onto the streets. Reality, however, is quite different from the imagination. RJB has mentioned in interviews his frustrations with trying to get his more racy designs printed onto shirts in the States, but his depictions of blond women in Daisy Dukes with pouting lips and rollerskates earned him a following in Japan. If there was to be an inverse to Rockin’ Jelly Bean, it would be Simone Legno, AKA Tokidoki, the Italian artist that produces Sanrio inspired artwork and goods with anthropomorphic sushi and rail-thin Japanese women in in sleek mod inspired clothes, the antithesis of RJB’s choice of leather, 70’s kitsch fashion, or no clothes at all. Meanwhile RJB’s art has been used for American movies (Guardians of the Galaxy), American brands (a series of Dr. Pepper cans in 2006) and western bands (t-shirts for the Rolling Stones). The grass is always greener and the women always appealing to your particular fetishes on the other side of the border.

In interviews RJB stated that drawing manga was a career he gave up in childhood, but his output as an illustrator is certainly prolific and one can also see how certain manga authors have left a deep impression on RJB’s style. Recently he has contributed to an art exhibition celebrating Buichi Terasawa’s pulp sci-fi romp, Space Adventure Cobra, and has also spoken at length about Go Nagai’s horror tinged hero, Devilman. These are manga cut from a similar cloth: garish over the top heroes, hyper sexuality tailor made for teen boys, and explosive action, all of which is embodied throughout RJB’s posters and illustrations. For Devilman, RJB reimagined the winged anti-hero as a drooling creature reminiscent of Ed Roth’s Rat Fink, sitting atop of a colossal hot rod. RJB’s version of Cobra is not as much a departure from Terasawa’s vision. Devilman is a creature, so it’s only natural that RJB interprets him as something from a more familiar bestiary, but Cobra’s style is rooted in the style of cinema (the hero is based on actor Jean Paul Belmondo), which is echoed by RJB’s movie poster art style. He has also put his unique spin on the likes of Godzilla, Neon Genesis Evangelion, and Street Fighter, imprinting on these Japanese mainstays of pop culture a lurid coat of paint rooted in American exploitation style.

RJB’s talents were also leant to a series of sculptures based on American comic book properties. Mystique, the azure femme fatale of the X-Men, and Warren Comics’ perpetual bloodsucker, Vampirella, got rendered in plastic based on RJB’s designs. While artistically these figures are certainly departures from the likes of John Byrne and Frank Frazetta, they mostly just amplify aspects of those characters that they’re already known for: sexy action women from comics. However, it’s RJB’s interpretation of Sue Storm, the Invisible Woman of Marvel’s First Family, the Fantastic Four, that really turns heads. A character that started out drawn by Jack Kirby with a modest flip hairdo and a not-particularly-form-fitting onesie, was transformed by RJB to have Farrah Fawcett-esque locks cascading down a back that is impossibly arched as every inch of her Unstable Molecule infused costume emphasizes her hyper-exaggerated curves. RJB transformed Marvel’s matriarch to an Oedipal fetish-totem of teenaged desires. And teenaged desires are indeed at the heart of Rockin’ Jelly Bean’s work, for better or worse.

Most recently Rockin’ Jelly Bean has contributed to the art book Tokyo Sweet Gwendoline, which partners him up with gynoid imagineer Hajime Sorayama, and monster master Katsuya Terada.

Subscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …