Your Cart is Empty

Artists

Shintaro Kago: Decrepitude & Absurdism

July 28, 2021 4 min read 0 Comments

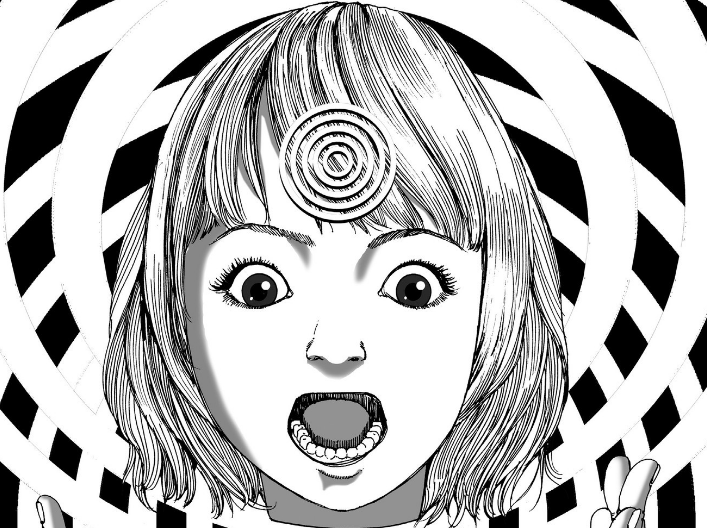

Sitting in a dormant part of my hard drive is a simple image, dated from around 2007, of bold white text on a black background that simply says “SHINTARO MOTHERFUCKING KAGO”. A picture passed around on /a/ and other pockets of the web that circulated the work of Shintaro Kago, it’s not exactly an elegant proclamation of love for the author, but it did get the point across to those familiar with Kago’s work. Shintaro Kago has been professionally creating manga since the late 1980s, and he was formally introduced to the English speaking world in the long out-of-print and now venerated tome, Secret Comics Japan, back in 2000. Kago’s work has often been been classified as an ero-guro (erotic grotesque) artist, due to his frequent depiction of sex and gore, though this term has never sat right with me. While it’s undeniable that Kago produces images that are grotesque and erotic in nature, the term ero-guro has become broad enough to refer to artists that do Taisho-era throwback stylization, such as Suehiro Maruo, and those that go for slasher movie gore coupled with sugary anime cuteness, such as Waita Uziga. Kago has a dark sense of humor coupled with an eye for detail reminiscent of a Bosch painting. Kago will draw military vehicles made of human body parts that propel via streams of shit with the same matter-of-factness that a 7-11 presents a hotdog. The scatalogical is a recurring theme through Kago’s work, as every manner of bodily fluid cascade across the page in a Bellagio fountain-like display. Kago has even organized a film festival revolving entirely around depictions of poop called The Unco Film Festival, which has featured artists and filmmakers around the world. Kago’s art does not revel in cruelty so much as in absurdism and an inherent humor to his work that endeared him to fans around the world. Kago sells portrait commissions on his Twitter account and many fans (including a few friends of mine) have commissioned him to draw their loved one’s heads being cut open like a birthday cake or having a pet cat feast on their brains. Nothing is sacred and nobody comes out of a Kago manga with their dignity intact as the human body is routinely broken down, reassembled, transformed, and transfigured by the expectations of society. This is emblemized in Kago’s comic, Dementia 21.

Dementia 21, published in the United States by Fantagraphics Books, is an absurdist skew on the care of Japan’s eldery, their place in society, the strain on families, and the progressing decrepitude of the human body. It’s a subject matter that’s pretty grim, and one many people have had experience with. Dementia 21 satirizes the sort of commodification and quantification of life and how every effort is made to “fix” the issue of the elderly rather than actually coming to a place of understanding or respect. Characters exist in a perpetual cycle of abuse and spite and the elderly switch from victim to victimizer from chapter to chapter as adult children resent the burden of their elderly parents and the elderly lash out at children for failing to live up to expectations. Yukie Sakai, our heroine, is a plucky caregiver who dedicates herself wholeheartedly to caring for the elderly so she can get a high enough score within her company. Because of this dedication she bends herself over backwards as she is handed extreme cases, such as caring for a household where the octogenarian occupants seem to double daily, and a driving obsessed old man that insists on speeding along the highways. Kago uses the elderly as a means of reflecting not just Japan’s aging populace, but also its aging pop culture, infrastructures, and more. In one chapter Yukie is tasked with caring for Redman, a parody of tokusatsu heroes like Ultraman. Still colossal in size, Redman too grapples with memory loss, creaking bones, and struggles with going to the bathroom as his former adversaries and alien invaders also succumb to osteoporosis. Dementia 21 depicts life as an unending series of bureaucratic establishments holding sway over our lives and bodies. Kago takes multiple jabs at test-obsessed society where one story involves training for caregivers who have to carry dummies representing their charges through jungles and snowy mountains, and another story where the elderly take a standardized test to become “Professional Senior Citizens” and must display an exemplary amount of decrepitude and interest in elderly hobbies. The idea of life as a perpetual series of mandated tests is more gruesome than any depiction of body horror this book could throw at me. This paints a pretty grim picture of Kago’s world in Dementia 21, but this is coupled with Kago’s colossally scaled absurdism, taking these themes of parental abuse and mental collapse, and turning them into spectacles reminiscent of B-movies.

Kago’s art is as messy as it is intricate with his depictions of crisscrossing wires through hospitals, overlapping highways (with lanes designated for drunk drivers, elderly drivers, and suicidal drivers) and landscapes of wrinkled skin. This cacophonous assault on the senses has led some to call Kago’s style “fashionable paranoia”, though the precise originator of this term is unclear, and in an interview conducted by Gary Groth, Kago seemed nonplussed by the term. Kago prefers the moniker of “kisou (bizarre) manga”. There is an undeniably fashionable element to Kago’s work, whether he’s aware of it or not. His sensational cover for a February 2008 issue of Vice and his art now appears on streetwear. This difficulty in defining what Kago’s manga is is a factor in his mystique and appeal. Kago’s art reflects a pervasive sense of paranoia and the general absurdity of daily life in society through a mirror of comically bizarre art.

Subscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …