Your Cart is Empty

Artists

The Nirasawa Filmography: Deep Fear

January 25, 2021 3 min read 0 Comments

During his artistic career, Yasushi Nirasawa has done concept art for video games going as far back as the early 90s with Beast Wrestler on the Sega Genesis. By 1998, the world of games was evolving to new narrative and visual heights. Colloquially considered one of the best years in video game history, it includes titles such as Half Life, Parasite Eve, Metal Gear Solid, and Resident Evil 2. It seems many games from 1998 emphasized high production values, cinematic action, and bizarre body horror elements, and Sega was looking to combine these components their own way. Deep Fear, published by Sega and released in Japan in 1998 (a scant few months before the release of the Dreamcast) and Europe the same year (it never saw a release in the United States), was simultaneously ambitious and painfully derivative.

An underwater military facility which also houses a tech company, a rescue team, and an agricultural firm, is visited by a chimp who has returned from 40 year journey in space imbued with space-radiation, while an accident with a submarine causes the space radiation to hit a secret research lab on the base, leading to the place being overrun with hideous mutants. This amounts to a game that is a little bit The Thing, a little bit The Abyss, and a LOT of Resident Evil. Mired by clichés and an abundance of sub-par voice acting, Deep Fear doesn’t exactly lay on the charm, but it does have some interesting looking creatures.

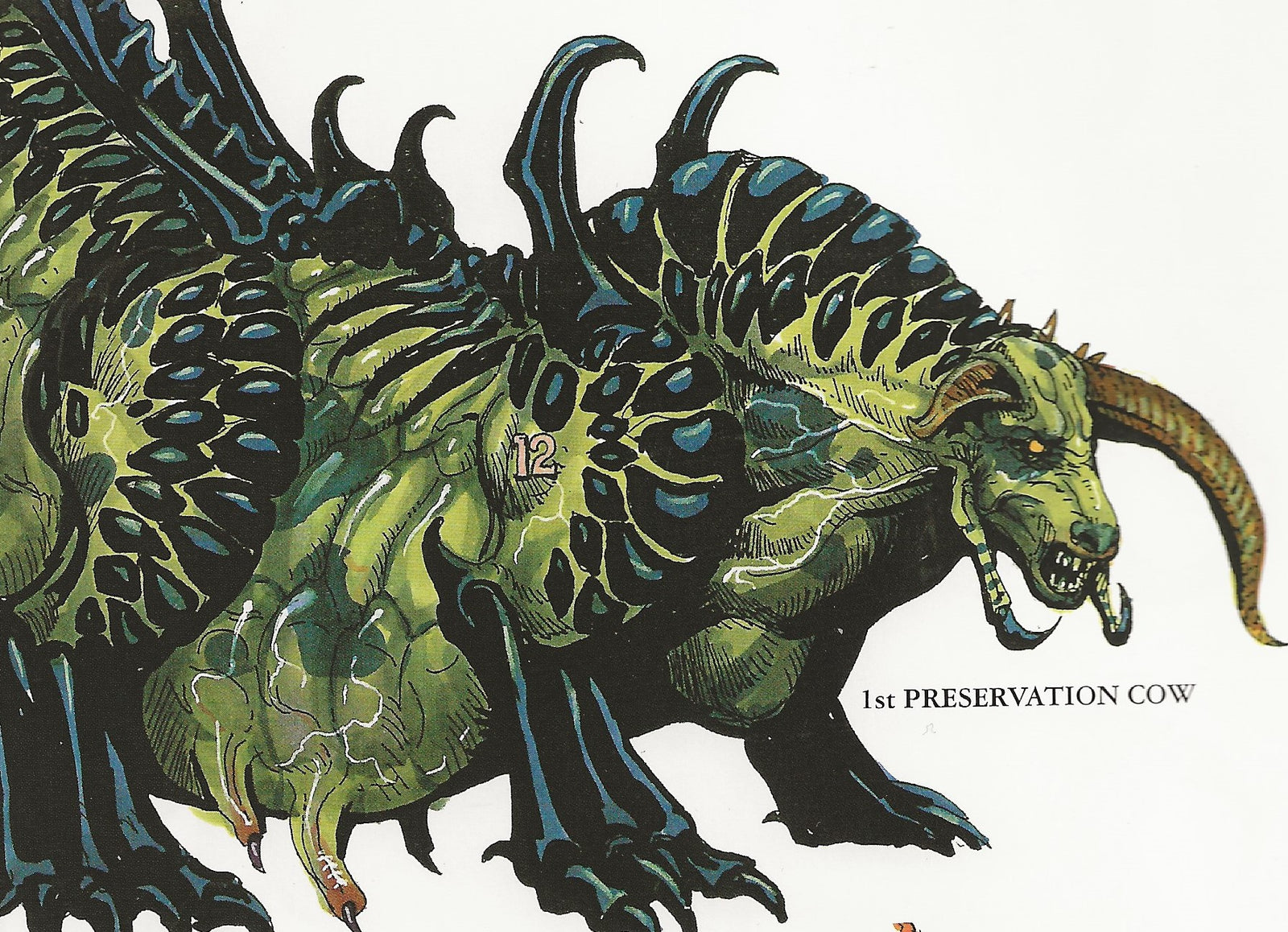

Containing a heavy body horror element, Nirasawa was a natural choice to design creatures for this game. The art book Niragram goes into Nirasawa’s difficulties in designing the creatures in the game, and having to balance Sega’s contradictory demands that the monsters have elements that occur in nature, and to also give the monsters iterating generations that look different, but also have similarities. To the best of Nirasawa’s ability his characters that are humans transforming into creatures recall the mid-transformation sequence of An American Werewolf in London, where human features are visible, but being stretched and pushed away and a bulbous new monstrous form emerges. There is a motif of asymmetry as bodies are consumed and transformed by mutating organisms that recalls The Thing and The Fly. While Nirasawa’s design work here is ambitious, the game fails to do it justice.

A late release Saturn game, it’s clear that Deep Fear pushed the system to the limits of its hardware, with sprawling maps, voiced pre-rendered and in game cutscenes, and a real attempt to bring Nirasawa’s art to life, but in the end the results aren’t entirely satisfying on a visual level. It’s one thing to get a Nirasawa drawing translated to a sculpture, but getting that drawing translated into a 3D computer image on a system primarily designed with 2D in mind is an uphill battle. Nirasawa wrote that his favorite design was the Soldier, an asymmetrical mass of translucent flesh bags, claws, and tendrils that looks simultaneously delicate and fearsome like a deep sea jellyfish. Unfortunately, such minute details aren’t well conveyed on the Saturn’s hardware and it just looks like a bunch of blue rocks on legs.

Despite a few nice looking CG cutscenes, the animators just can’t do the designs any justice. In one scene a villain attempts to make an escape, but is cornered by one of the creatures, a hulking humanoid with a rippling muscular physique, horrific mandibles, and a gigantic clawed arm. Does the monster impale the man with the enormous claws? How about crush his skull and feast on the gooey insides? Nope. The monster just kinda stands there and limply raises his arm, and drops it down, then raises it again, utterly devoid of fluidity, dynamism, tension, or terror. While Nirasawa’s art design certainly elevates this game, it can’t carry it. Ultimately Deep Fear was quickly and quietly relegated to the dustbin of gaming history. Luckily this would not be the last game Nirsawa would lend his talents to.

Subscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …