Your Cart is Empty

Artists

The Super Creators: Shigeru Mizuki

June 08, 2021 4 min read 0 Comments

One of the legends my great-grandmother took with her from Italy to America was that of a werewolf who lived in her village. A man who turned into a beast and “tumbled through the streets” (her words), until he returned to his family home by knocking on his front door in a certain way to ensure the people inside he was no longer a creature. Perhaps you have a similar story from your own family that you can brush off as an exaggeration, but makes you ponder “what if?” in the dead of the night. Shigeru Mizuki made a career in comics by being the steward of such stories.

Shigeru Mizuki (1922 - 2015) was one of the great storytellers of manga, who even made Osamu Tezuka bristle with jealousy. Growing up in the coastal countryside of Sakaiminato, many of Mizuki’s stories draw from legends and folklore passed down through generations. Stories of Betobeto-san, who would leisurely pursue travelers on lonely roads, Nurikabe the invisible wall, and the long tongued Akaname whose claws would click-clack against floorboards. This would lay the foundation for his most famous work, Gegege no Kitaro (more on that later). Mizuki’s Nonnonba (published in Japan in 1992, and translated into english in 2012) recounts his childhood far removed from the city life and how tales of yokai (assorted Japanese spirits, demons, and creatures) were passed down to him. But the outside world for a way of breaking into Mizuki’s life as it did for so many others. In 1945 Mizuki was drafted into the Japanese military and was stationed in New Guinea. Mizuki had a keen interest in the arts from an early age, but during an Allied bombing raid he lost his left arm, which happened to be the one he used for drawing, necessitating him to almost completely re-learn his craft. Subjected to the horrors of war and disease during World War II, Mizuki used his experiences as the basis for his historical comics later in life such as Onward Towards Our Noble Death and Showa: A History of Japan. These experiences (including being ‘ordered to die’ by his commanding officers) did not break Mizuki, and if anything, fueled his resolve to create a world removed from the blight of war. Confronted by the cruelty of man, Mizuki looked to the world of the supernatural as an alternative.

Mizuki’s most famous creation is the manga series Gegege no Kitaro, a manga series which initially ran in the 1960s. The series has endeared itself to the point where there have been animated adaptations decades after the end of the original manga, statues of Kitaro dotting Japan, and a brand of sake available at your local Japanese grocer. The creation of Kitaro is tied to the all but lost art of Kamishibai, stories told by street performers who displayed large illustrations while providing voices and narration. These stories served as the foundation for everything from tokusatsu heroes such as Kamen Rider, to the erotic-grotesque horror of Suehiro Maruo’s Tsubaki Shoujo. Before the rise of television and manga, Kamishibai was a popular form of entertainment for children in Japan, especially during the Great Depression. Kitaro was a character created by Masami Itō for his stories Hakaba Kitaro during the 1930s and was a sort of amalgamation of various Japanese legends and folk tales. After World War II, Mizuki started adapting these Kamishibai stories to manga, adding his own touches and characters along the way. Despite being one of the all-time great works of manga, Kitaro was not readily available in the states until 2013 when Drawn & Quarterly began to translate selected chapters.

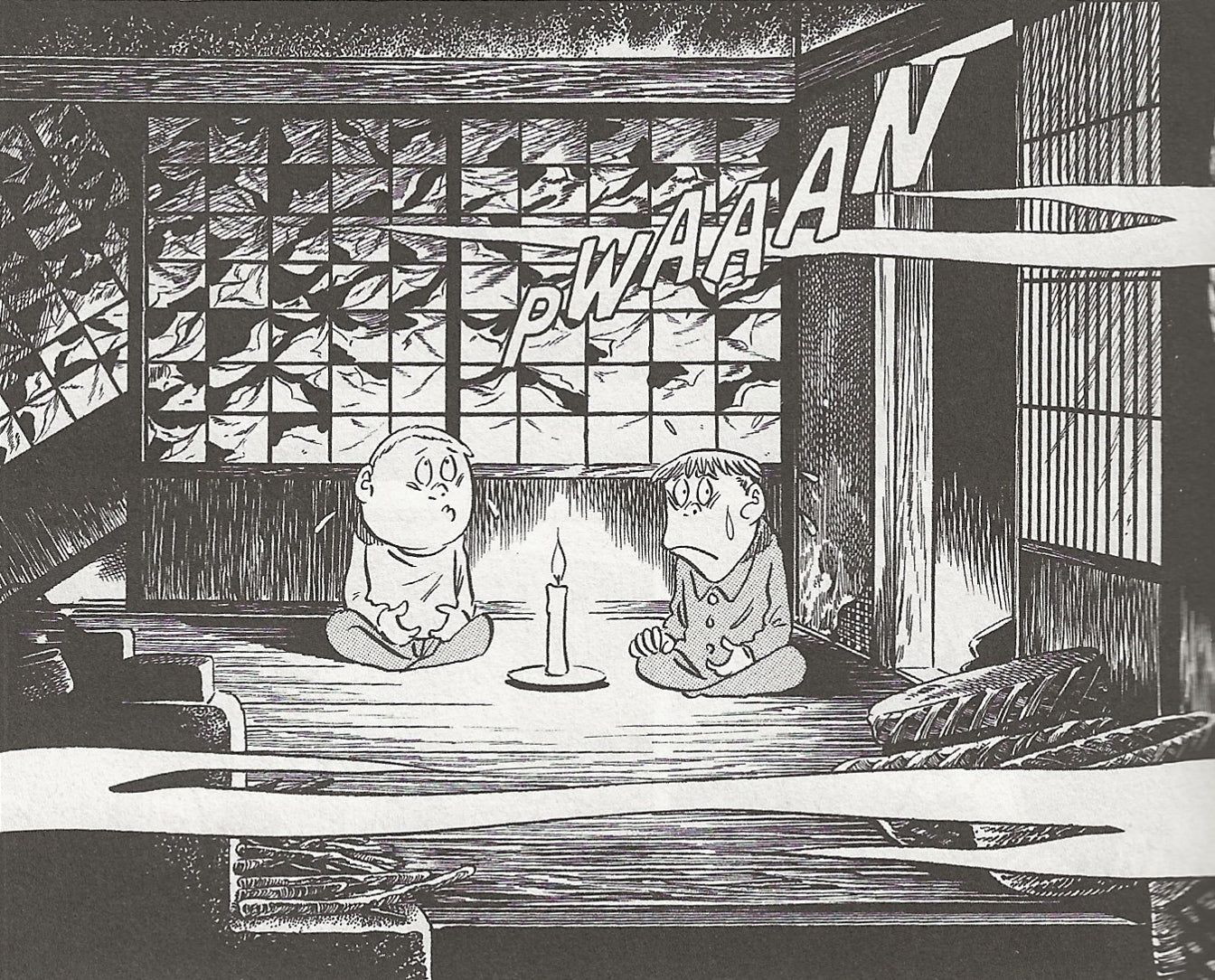

Kitaro is a small boy that watches over the people of Japan with his bizarre powers as a sort of anti-cherub. Diminutive, cycloptic, and unwashed, Kitaro doesn’t fit the model of what is typically considered a “superhero” in the US, but all the same he uses his amazing supernatural powers to protect humanity and maintain balance between the human world and the domain of yokai. There’s a madcap absurdity to Mizuki’s Kitaro stories that make them nearly impossible to predict where they will go next. A guitar-strumming vampire hypnotizes a rat-man in a glitzy Ginza cafe, a giant cyclops demands errant children attend his school in a secluded mountain, spirits gather in a graveyard for a baseball game. There’s an earnestness to Mizuki’s work that avoids being too maudlin or schmaltzy, and many times the stories don’t have any moralizing beyond Kitaro dispelling some threat, but there’s a versatility in how Mizuki uses yokai. Sometimes the yokai of Kitaro’s world reflect humanity’s greed and capriciousness (especially Nezumi-otoko, who almost routinely betrays Kitaro), while at other times they’re nature's wrath towards an overly complacent mankind. And yet other times they embody an idyllic rejection of capitalist modern societal values, as the yokai predate currency and carry on just fine without it.

Shigeru Mizuki’s manga such as Kitaro, Nonnonba, and Onward Towards Our Noble Death are published in the United States by Drawn & Quarterly, and the 2018 Gegege no Kitaro anime series is available on Crunchyroll.

Subscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …