Your Cart is Empty

Artists

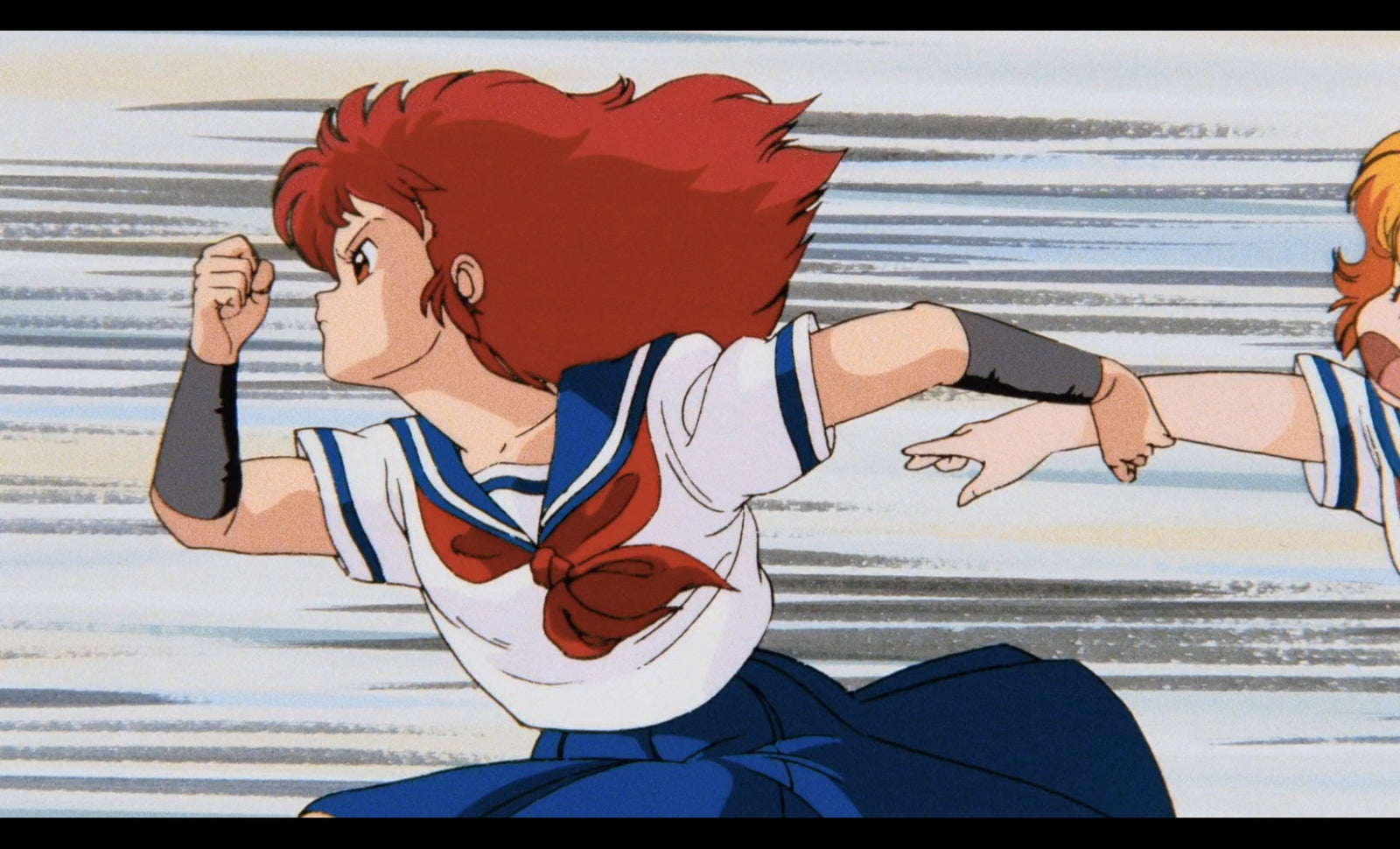

Review: Project A-Ko on Blu-ray

March 04, 2022 4 min read 0 Comments

Often our fond memories of cartoons or movies from our youth are protected by the haze of memories, and we have to decide whether to keep it tucked away in that fond miasma or bring it back out for reappraisal. This all sounds very weighty, but I’m talking about a cartoon where schoolgirls perform wrestling moves on giant robots. When I first saw a preview screening of the restoration of Project A-Koat Otakon 2021, it was with some trepidation. Would this seemingly frivolous anime from 1986 still hold up? Now that this restoration has come home on Blu-ray, Project A-Ko manages to still be a spectacular work of ribauld excess, thanks to some genuine care and restoration work from Discotek Media. A small, but dedicated company, over the years Discotek has become a darling to aficionados of classic anime. Often drawing comparisons to the Criterion Collection, Discotek strives to have the best image quality possible in addition to extras for titles such as Lupin III Castle of Cagliostro, Robot Carnival, and Memories.

The titular A-Ko is a schoolgirl with superhuman strength, who draws the ire of rich girl B-Ko, who wants to have the affections of A-Ko’s close friend, the loud yet compact C-Ko. Amidst this schoolyard rivalry there’s also giant robots, power armor, futuristic cities, and alien invasions. A send up of anime clichés and motifs, A-Ko was theatrically released in Japan in 1986. In 1991 the film would finally make its way to the US on VHS in what would turn out to be a pivotal time for anime in America. The early 90s were a transitional period for anime in the United States. Before then exposure to Japanese animation was either heavily altered kids’ TV shows (Star Blazers, Battle of the Planets, Voltron) or clandestine screenings of films at sci-fi conventions that necessitated live narration due to lack of subtitles. 1991 was also the same year Akira came to home video in the United States, followed by the emergence of ADV and Streamline Pictures. Anime was establishing its foothold in American pop culture, and Project A-Ko was the vanguard, a candy-colored assault on the senses that was incomparable to anything else populating the shelves of American video stores. Project A-Ko is the sort of ur-anime that, through its spectacular visuals and absurd humor, solidified a certain conception of what anime is in the West, even long after Project A-Ko ceased being in vogue in Japan.

The original film negatives were considered lost for many years, and Discotek was making preparations to have the Blu-ray release be an AI upscale of the laserdisc version of the film, but in a stroke of luck it was discovered that the film negatives weren’t lost so much as misfiled for a few decades. There is a frantic level of detail that can now be appreciated thanks to this release, from intricate mechanical details to minor gags that even the most eagle-eyed viewer wouldn’t be able to catch on VHS. On top of this is a plethora of extras and archival galleries featuring model sheets, promo materials, and behind the scenes info on the film. One of the most interesting features is a series of new interviews with producers/songwriters Richie Zito and Joey Carbone, and singers Annie Livingston and Samantha Newark, all of whom contributed to the film’s soundtrack. If you ever wonder why the film opens with a Giorgio Moroder style beat, this featurette dives into the film’s musical DNA.

In addition to the Japanese audio track and the classic dub that got much TV play, this Blu-ray includes the film in its widescreen 16x9 theatrical format, as well as the 4x3 open-matte version of the film, two audio commentary tracks, and and storyboards and animatics can be played alongside the film. A common feature in video games from the 80s and 90s being re-released on modern consoles is the inclusion of artificial scanlines to simulate the feeling of playing the game on a CRT television. Project A-Ko, as a film, was produced with the intention of being shown in a movie theater, but over the decades most people have interacted with the film on TV sets. It’s probably logistically untenable, but it would be a nice extra if older anime like Project A-Ko had a setting that put filters over the image to simulate a worn tape being played on an old Zenith TV. As tempting as it would be to evoke childhood memories of how anime once appeared to us, that would be doing a disservice to the absolutely stellar work of the animators on this film and the hard work Discotek has put into restoring it. The box calls this the “Perfect Edition” and it delivers on that claim.

While working on this review I had a sort of epiphany. A few weeks ago I went to The Metropolitan Museum of Art and saw their exhibit Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts, which featured the work of Mary Blair and Marc Davis, among other Disney luminaries from decades past. Disney considers their work important enough to be displayed at one of the most important museums in the world, yet their own home video releases practically destroy the detail in these films. Discotek doesn’t have more money than God and an ever growing media empire, but they have a wealth of genuine care and appreciation for animated films.

Subscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …